The principles of ‘I-We-You’ are central to my maths teaching: give children the tools to think with clear models and examples; build understanding and address misconceptions in the guided practice; then children work with high success in their independent practice.

Issues can arise, though, if an ‘I-We-You’ approach leads to a more procedural approach to teaching. Mathematics is not about following a set of pre-determined instructions. I might need a prescriptive approach if you are teaching me to wire a plug. Step-by-step instruction can help me to learn how to do a column subtraction. But it isn’t how I can become a mathematician. And it won’t lead to me becoming emotionally invested in my mathematics. Maths lessons should allow children to play around with key ideas, become curious and make connections.

There is another big challenge in the ‘We’ phase of the lesson. How can we provide questions/tasks that build understanding and extend thinking for all children? If children are given a question to answer in the ‘We’, some children may finish almost immediately. Other children may need more time and more scaffolding.

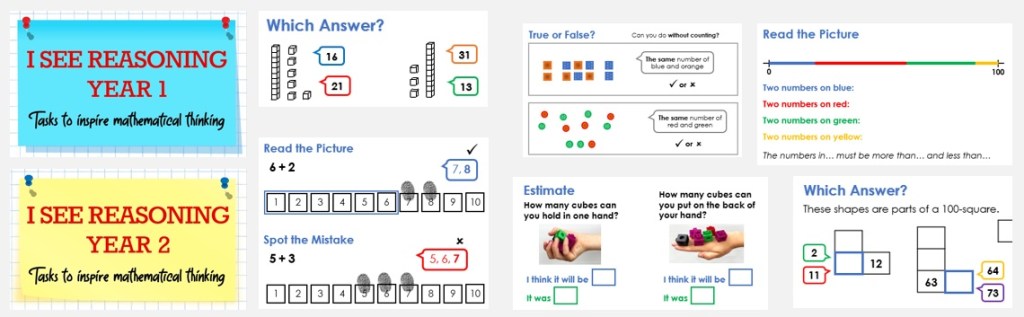

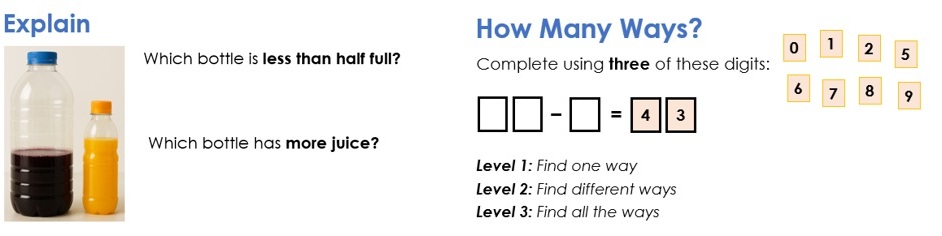

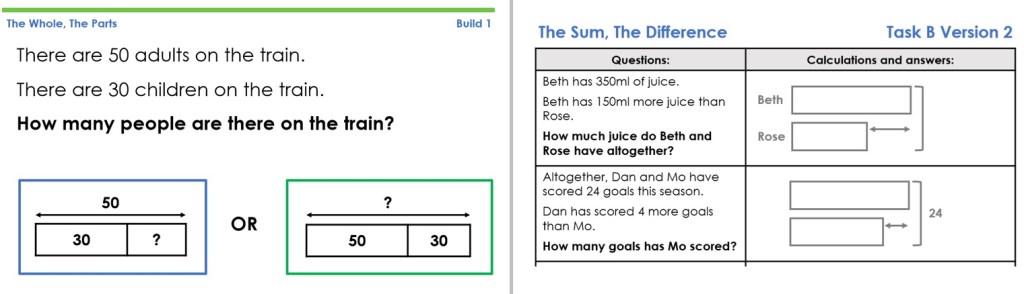

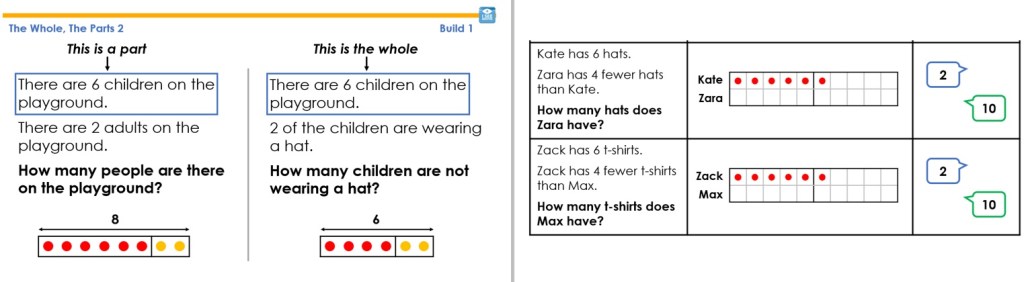

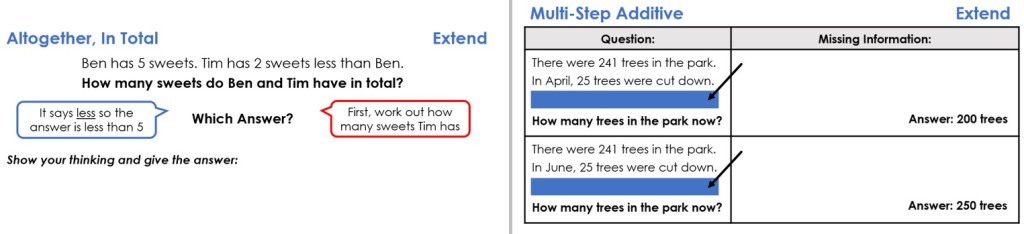

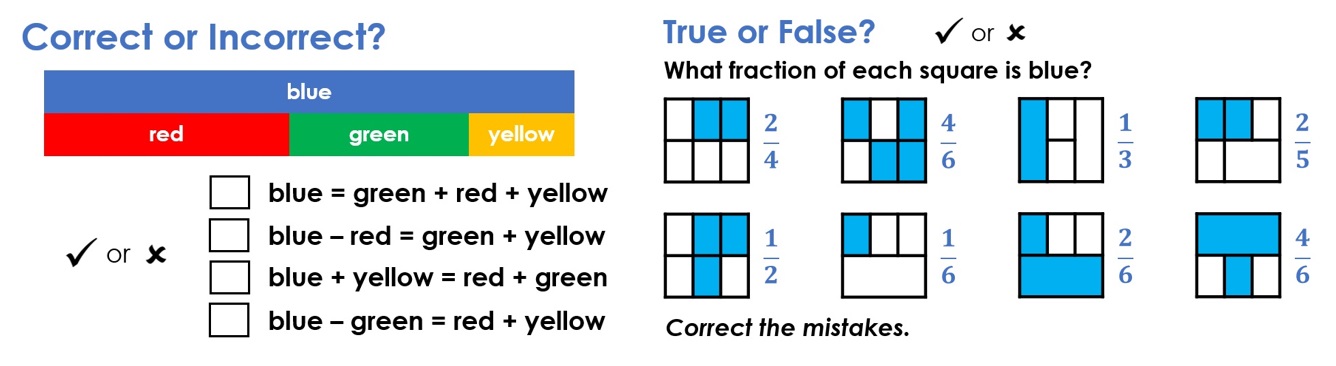

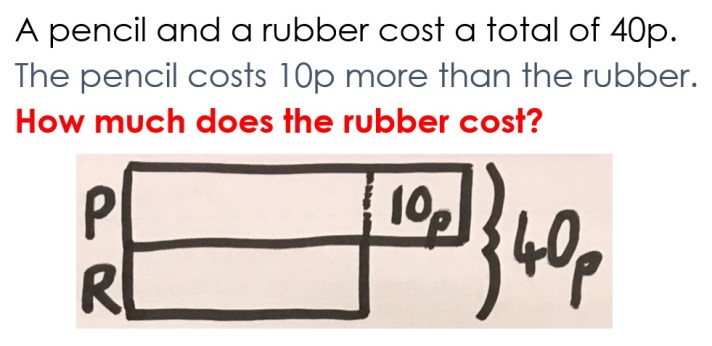

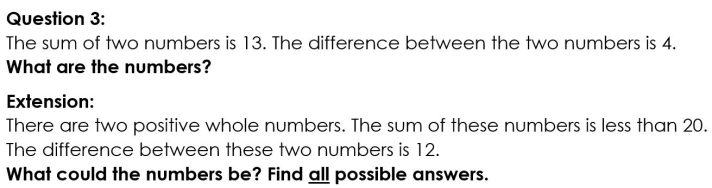

How can we hold all these ideas together? Is it possible to provide high-quality modelling and engage children in effective guided practice, whilst allowing space for children to be curious and make their own discoveries? I believe we can! In the ‘I’, think about exploring concepts rather than modelling steps. For questions in the ‘We’, think about using the slow release of information (the subject of this blog) or using pairs of questions (the subject of a future blog) to engage all children in discussion. Consider the question below:

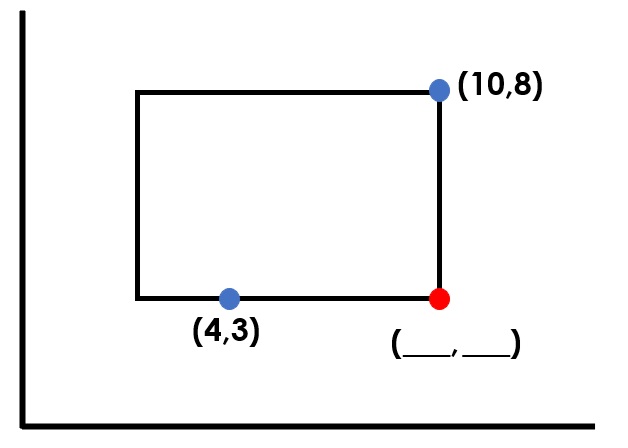

Following an ‘I-We-You’ approach could mean modelling two questions that are near-replicas of this one. Then, I could give this question to the children to answer on their whiteboards. What problems do I see? Firstly, some children will be able to answer this question within seconds. The rest of the class, then, feel a pressure to catch up. Speed is emphasised, the answer becomes the focus. Secondly, will the children be able to answer a different coordinates question when the ‘steps to success’ no longer apply?

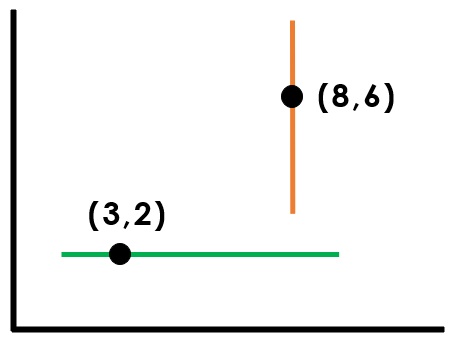

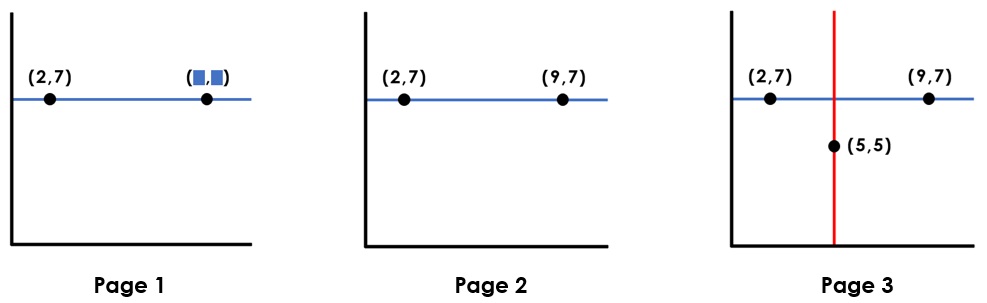

Here is a subtly different approach. In the ‘I’ phase, start by giving example coordinates that are and are not on the green and orange lines, noting the x/y coordinate that stays the same:

Then, looking at page 1 of the example below, I ask children to predict what the hidden coordinate could be, before revealing (9,7) and noting that the y coordinate is still 7. Next, introduce the red line (page 3). Ask children to predict which other coordinates could be on the red line. I could compare the positions of (6,4) and (4,6). Are they inside or outside of the bottom-left rectangle?

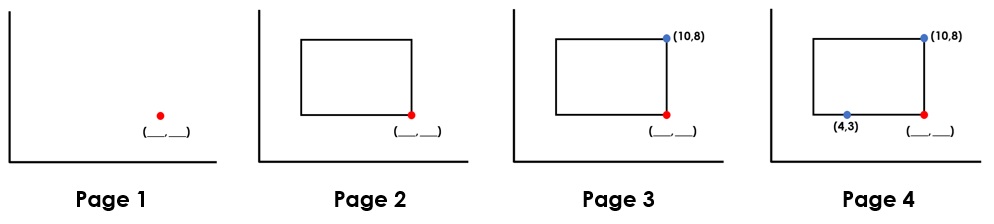

My main focus for this blog is to look at the slow release of the information for the question below, in the ‘We’ phase. Rather than presenting the whole question to the children, start at page 1. Ask the children what the red coordinate could/could not be. Note that x > y and spatially reason about the different possible coordinates. This acts as our estimate. Then, introduce the rectangle from the question (page 2) and ask the children ‘what information will we be given that will mean we can answer the question?’ Explore all possibilities. In doing so, children have the time and space to think about the structure of the task before the question itself is introduced. The necessary information is slowly revealed (pages 3 and 4) and children can now give the answer having had time to think about the structure of the question. To extend, coordinates on the vertices, edges and inside/outside the rectangle can be given.

The power of the slow reveal is that children get to ‘play around’ with the big ideas before they have to give an answer. Children have more time to process the information, which is revealed in stages. Challenge exists as we consider ‘is that definitely what the missing information will be?’ Reasoning is emphasised and children use their imaginations!

Please share your thoughts, objections or related examples! Is there another maths curriculum area that you would like me to consider on a future blog? Or other similar example tasks that you could share? I hope that this blog can spark some interesting conversations and collaborations!