In the early 20th century, psychologist Lewis Terman carried out a now-famous research project: he aimed to prove that by knowing a person’s IQ at an early age, you are able to accurately predict his or her life success. Using a series of intelligence tests, he identified an elite group of 1,470 children to study. Terman believed that it was these children (and others of extraordinary IQ) that ‘we must look for production of leaders who advance science, art, government, education and social welfare generally.’

Terman carefully monitored the progress of the ‘Termites’ over a period of 35 years to ascertain their life success. The results surprised many, including Terman himself. The group thrived in many ways, most notably being healthier, taller and more socially adept than the average American. However, their achievements were far from remarkable. In fact, a later study concluded that a random sample of people, given the same socio-economic status, would have achieved just as well. Terman himself reluctantly concluded that ‘intellect and achievement are far from perfectly correlated.’

Later studies went on to explore this idea more thoroughly, as explained in Malcolm Gladwell’s book Outliers. Generally speaking, people who achieve great professional success have an above average IQ: usually 115 or above. However, beyond this ‘intelligence threshold’, a person’s success is determined far more powerfully by other skills and attributes rather than the full extent of their IQ. Gladwell argued that it is hard to be highly successful without above average intelligence; however, beyond the intelligence threshold success is determined by other factors, for example the character and inter-personal skills of the individual.

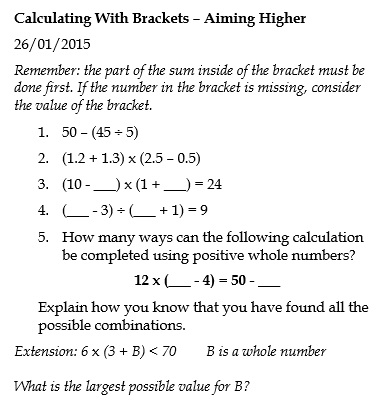

Pupils who grasp concepts rapidly should be challenged through being offered rich and sophisticated problems before any acceleration through new content.

National Curriculum, Maths

This led me to think about the nature of the ‘rich and sophisticated problems’ that we should be providing. In order to equip children for long-term success, tasks should help children to develop personal and social skills as well as subject-specific expertise. Easier said than done for a busy and pressurised teacher!

That’s what I’m going to dedicate my working life towards: creating learning experiences in maths that engage children intellectually and emotionally; tasks create curiosity and lead to collaboration. I hope that this characterises First Class Maths, Maths Outside the Box and The Maths Apprenticeship.

I’m convinced that, if the system allows, these are the kinds of learning experiences that we as teachers want to provide for our children.