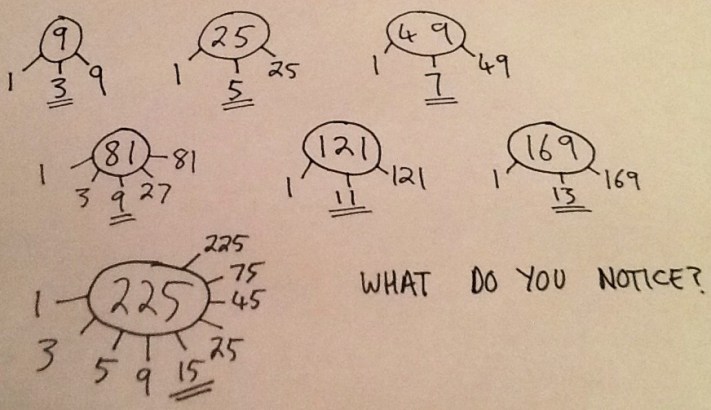

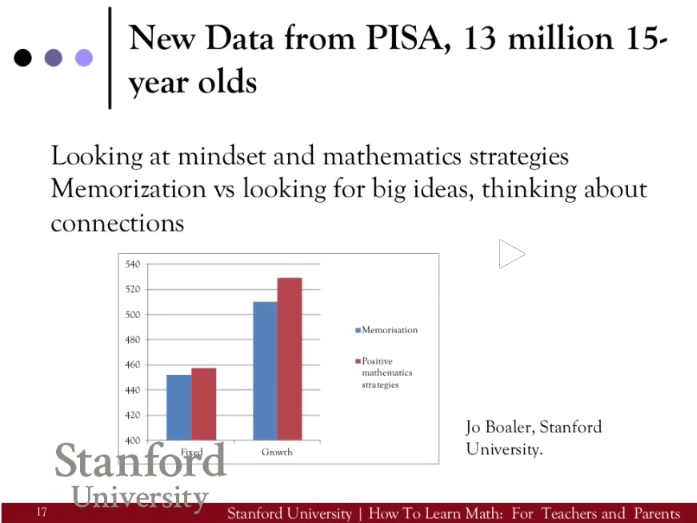

The new maths curriculum requires children to become fluent with number whilst developing the ability to reason mathematically and problem-solve. To achieve this, children will need a broad range of mathematical experiences. Here, I will share a small piece of this jigsaw: how a ‘traditional’ maths lesson – a lesson aimed at developing fluency – can be tweaked to incorporate reasoning and problem-solving skills.

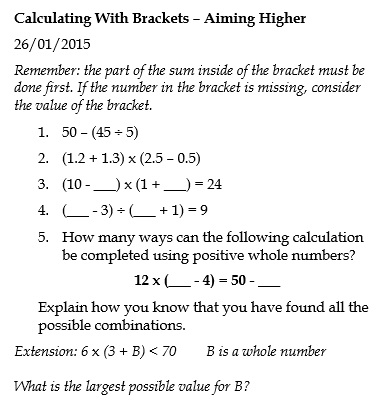

The procedural skill introduced in the lesson centred around the use of brackets. However, there are two fundamental mathematical principles that are also being developed here: the use of inverse, and the understanding of the = sign meaning ‘same as’ rather than ‘makes’. This is reflected by the questioning (mid level of difficulty) as shown below. There is a gradual progression in the structure and depth of the questions, challenging the children’s understanding of the concepts in a non-routine way.

Question 5 is then used to extend the reasoning element by using the ‘how many ways?’ structure. This challenges the children to work systematically to find all possible solutions.

Question 5 is then used to extend the reasoning element by using the ‘how many ways?’ structure. This challenges the children to work systematically to find all possible solutions.

These principles can be used for children of all ages. For example, presenting subtraction calculations in the following order will encourage children to reason about the underlying structure of subtraction:

13 – 8

12 – 7

11 – 6

Equally, consider how the following equation helps a child to develop their conceptual understanding of multiplication and of the = sign:

4 x 5 = 4 + 4 + 4 + 8

Also, the ‘how many ways…’ question structure is enormously adaptable, allowing you to build reasoning into maths lessons on a daily basis. I hope it’s a little technique that some people may find useful!